Deep Learning Hardware

Published:

Deep learning requires special kinds of computer hardware. This is a post about what makes that hardware so different from the traditional computer architecture, and how to get access to the right kind of hardware for deep learning. If you just want practical recommendations about how to get your hands on the right hardware, feel free to jump to the end. If you want to understand what makes GPUs (and TPUs) such a philosophically different approach to computing than CPUs, and why that matters for deep learning, then read on…

History

To really understand the difference between hardware that works well for deep learning and hardware that doesn’t, we need to cover some history. In the mid 19th century, there was a growing crisis in the mathematical world. The historical techniques that had worked well for reasoning about algebra and geometry were producing contradictions when mathematicians tried to apply them to some of the more subtle infinities and infinitesimals of calculus. So mathematicians started looking for new, more precise ways of reasoning that could resolve these contradictions.

This was the birth of modern formal logic. At its core, it was a way to translate math into strings of symbols, and rules for using prior strings of symbols to derive new strings of symbols that represented consistent statements about mathematics. You’re probably familiar with something very similar to this kind of deductive symbol processing from algebra:

\[\begin{align} x &= (4+5)/x\\ x &= 9 /x\\ x*x &= 9\\ x^2 &= 9\\ x &= \sqrt{9}\\ x &= 3 \end{align}\]Each step here is a string of symbols, and there are specific rules for how to convert from the string of symbols in one step to the string of symbols in the next step. For instance, to go from step 1 to step 2, we follow a rule that tells us we’re allowed to convert these five symbols: “\((4+5)\)” into this one: “\(9\)”. And similarly, to go from step 3 to step 4, we follow a rule that tells us we’re allowed to convert “\(x*x\)” into “\(x^2\)”.

Formal mathematical logic can be thought of as a generalization of this process, that allows one to express all of mathematics and all mathematical proofs as sequences of strings of symbols, where each string was derived from prior strings in accordance with rules of symbolic deduction. As mathematicians understood how these systems of symbolic logic worked, they started describing such systems in terms of machines that could perform the operations that would transition from one string of symbols to the next. These theoretical machines were the basis of modern computers. In fact, most computers built today still roughly follow the general architecture laid out by the mathematician, John von Neumann, in 1943.

von Neumann Computers and Central Processing Units (CPUs)

The von Neumann architecture consists of a few basic building blocks:

- Input - This is a way for a person to give the computer data and instructions for processing that data. On modern desktop computers, this might be a keyboard and mouse, and on servers, this might be a network connection that takes requests.

- Memory - This is where the data and instructions are stored. Today this means both RAM and Hard Drive. RAM is much faster than hard drives (usually thousands of times faster), but it’s not able to retain information without a constant supply of electricity. So long term storage is on hard drives, and short term storage is in RAM.

- Output - This is how the computer returns the results of the computation. On a modern desktop, this would be a screen or speakers. For a modern server this would be a reply sent through the network connection.

- Arithmetic Unit - This is what actually performs the symbolic manipulation to go from one or more strings of symbols to the next string of symbols.

- Control Unit - This keeps track of which string(s) the Arithmetic Unit needs to process for the current step.

Today, the Arithmetic Unit and Control Unit are bundled together into a “Central Processing Unit” or CPU.

The von Neumann architecture, and von Neumann-style CPUs in particular, are excellent at performing the kinds of sequential symbolic processing that computers were originally designed for. This worked well for many years while the primary computer interface was a prompt where the user would input a string of symbols, which the computer would process to calculate the next string of symbols.

Eventually though, it turned out that formal logic was only a tiny fraction of the diversity of ways that human beings engage with information (who knew?!), and it wasn’t long before people wanted to use these new, fast electrical information machines for more diverse tasks. So the Graphical User Interface (GUI) was born:

With the growth of graphical interfaces, CPUs were used to compute more abstract and complex things than before, including windows and icons on higher resolution screens. This was only possible because the CPUs of the early 1980s had become fast enough to perform millions of symbolic processing steps per second.

For a number of years, transistor sizes shrank according to Moore’s Law, and CPU speed continued to increase accordingly. And so CPUs were able to draw more and more complex and rapidly changing user interfaces including many video games. But ultimately, this was a hack. The basic design of CPUs was developed by mathematicians to perform the kind of sequential symbolic operations that happen in mathematical proofs, which are a profoundly different kind of task than drawing complex and rapidly changing images on a screen. As the video game industry took off, it was clear that CPUs could not perform sequential operations fast enough, and a new type of parallel computational unit would have to be invented. And so the Graphical Processing Unit (or GPU) was born.

Graphical Processing Units (GPUs)

GPUs were a fundamental departure from the von Neumann architecture. Where CPUs were designed to operate on strings of symbols, performing one computation at a time, GPUs were designed to operate in parallel on huge collections of numbers to calculate whole expanses of a visual field simultaneously. But GPUs were originally thought of as just a tool to draw pictures on the screen.

Additionally, the long history of von Neumann computers meant that the majority of programming languages were designed for such computers. Today this includes languages like C, C++, Java, Javascript, Python, Swift, Go, Ruby, Rust, etc. Since these programming languages were all designed for von Neumann computers, this means that all of the software written in these languages runs on CPUs. This includes every major operating system, every word processor, every web browser, every email client, etc. This software legacy means that any GPU attached to a modern computer will be a peripheral component. And today, GPUs connect to traditional CPU-based computers using a protocol known as PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect).

In servers and desktops, a GPU is one or more chips attached to a physical expansion card known as a “graphics card” or a “video card”. These expansion cards get their name from their card-like shape, which plugs into a PCI slot on a computer’s motherboard:

In laptops, televisions, smart phones, and smartwatches today, there are no PCI slots and consequently no expansion cards to plug into them. People do still sometimes refer to GPUs in laptops as “graphics cards” out of habit, even though this is technically inaccurate. Laptop GPUs are soldered directly onto motherboards as shown here in red:

The computing paradigm of GPUs was so radically different than traditional CPUs that GPUs were originally largely isolated from the software running on CPUs. GPUs were only exposed to such software via higher level graphics APIs designed for rendering images on screens. Eventually, though, GPU manufacturers started to understand the unique computational power of GPUs, and they created programming languages like CUDA, with low level APIs for programmers to write code that could directly execute in parallel on GPUs.

The subsequent shift from von Neumann style symbolic processing CPUs to massively parallel calculations on GPUs was the core technological advancement that made the modern Deep Learning Era possible.

Deep learning is inspired by the neural information processing patterns of the human brain. And human brains are fundamentally not von Neumann machines. Human beings evolved from single cell organisms and we inherited the cellular structure of most life on Earth. Evolution didn’t have high speed, high energy silicon transistors available to build our brains, and formal mathematical logic wasn’t the top priority for the early stages of our ancestors’ cognitive development. We had to develop ways to use cells to perform analog, spatial tasks like moving toward light, or recognizing and fleeing from predators. And consequently, animal and human brains are large collections of cellular neurons that process information in massively parallel ways, much more like GPUs than CPUs. This is why GPUs are so much better suited for running software simulations of neural networks than CPUs are.

To quote Jeremy Howard, “When we say Python [on a CPU] is too slow, we don’t mean twenty percent too slow; we mean thousands of times too slow.”

Nvidia

While many companies today make GPUs for video games, one company in particular, Nvidia, realized the revolutionary importance of GPU computing for deep learning earlier than the others, and they prioritized making high quality programming languages and software libraries for deep learning tools to build on. In the video game space, AMD is the biggest competitor to Nvidia, and their GPUs have the hardware capabilities needed for deep learning, but the AMD software stack is nowhere near as robust as Nvidia’s. So nearly all modern deep learning libraries today are built for Nvidia GPUs.

At this point its worth mentioning that Python is a very popular language for deep learning. But Python runs on CPUs, not GPUs. What makes Python a viable candidate for deep learning is its ability to transparently call code written in other languages, including languages for GPUs. So for instance, in PyTorch when you see model.to(torch.device("cuda")), this is where Python is loading code written in CUDA into the GPU to execute there. If you run a PyTorch deep learning program without this line, you’ll find it’s thousands of times slower than with this line. This is because the code would execute on the CPU rather than the GPU.

Since nearly all deep learning libraries today are (ultimately) built on CUDA, Nvidia’s GPU programming language, this means Nvidia effectively has a monopoly on GPUs suitable for running deep learning programs. Interestingly though, Nvidia does not have a monopoly on GPUs capable of running video games. Nvidia must compete on price with AMD in the desktop/laptop GPU space, but doesn’t have to compete with anyone in the deep learning server space. This has led Nvidia to differentiate their GPUs into two lines: one for personal computers and one for servers. While these two lines are not drastically different in computational capacity, the licensing for the personal computer GPUs forbids using them in datacenters. This allows Nvidia to charge much more money for datacenter GPUs than it does for comparable personal computer GPUs.

Given how critical GPUs are for deep learning, one of the most important advancements for deep learning today would be porting deep learning libraries like Tensorflow to run on AMD GPUs. This would break Nvidia’s monopoly on commerical deep learning hardware and drastically drive down pricing.

So what should I do?

If you’re new to deep learning, you’re going to need access to some kind of computer with a fast Nvidia GPU. You can either access such a computer online through a cloud provider, or you can buy or build your own. As I described above, Nvidia has a monopoly on deep learning GPUs, so cloud providers will have to pay much more for GPUs in the datacenters than you would have to pay for a comparable personal GPU for your own computer. This might lead you to assume that buying your own computer with a GPU is the way to go. That would probably be true if not for Google. Google is offering very basic, and limited access to cloud servers with GPUs for the low, low cost of… NOTHING.

Google Colab

That’s right, Google has a cloud service called Colaboratory (or “Colab”, for short), which offers free access to basic GPUs, through a Jupyter Notebook interface for up to 12 hours at a time, for free. For someone just starting in deep learning, this is an excellent way to get easy access to a server with the right kind of hardware (and already pre-configured with the right software). The service offered through Colab is fast enough to start learning about deep learning, but there’s a good chance you’ll eventually hit the limits of what you can do with it. If those limits are primarily about speed, you can try upgrading to the $10/month Colab Pro plan which guarantees you faster GPUs and longer execution times.

Your own hardware

If you outgrow Colab, then it may be time to buy or build your own server. Rather than dig deep into the details of what GPU you should get, I’ll point you to Tim Dettmer’s excellent page, which he updates with each new hardware release. As of Spring 2020, Tim recommends an RTX 2070 for most newish users (or RTX 2080 Ti or potentially RTX Titan upgraded). These recommendations will likely change when Nvidia releases new video cards in mid-2020. If you would like to buy a pre-configured desktop or laptop, I would recommend buying from:

- System76 - They sell high quality Linux machines with options to add the kinds of GPUs you need for deep learning. This is a good source for a person wanting to break into the field.

- Lambda Labs - They sell high end deep learning workstations, preconfigured with multiple GPUs and deep learning software. This is a good source for a small business trying to start a small AI team.

If you want something a little cheaper and have a desktop around that you’re willing to run Linux on and install a GPU in, then you should go for Ubuntu Linux which is the most popular Linux used in AI today, or Pop!_OS, which is a compatible derivative of Ubuntu that has a lot of additional stuff built in to make it nicer to use. As for where to buy a GPU, Newegg amd Ebay, are both good choices. If you’re buying multiple GPUs to put in a desktop, make sure to buy “blower style” GPUs, which vent the heat out the back of the machine.

Cloud Services

If you outgrow a desktop or two, especially if maintaining the OSes on them becomes too complex, then you may want to consider renting cloud based compute from Google Cloud Platform, Amazon Web Services, or Microsoft Azure. Note that cloud based servers are much more expensive on an ongoing basis than running your own desktop, and they also use a completely different line of GPUs.

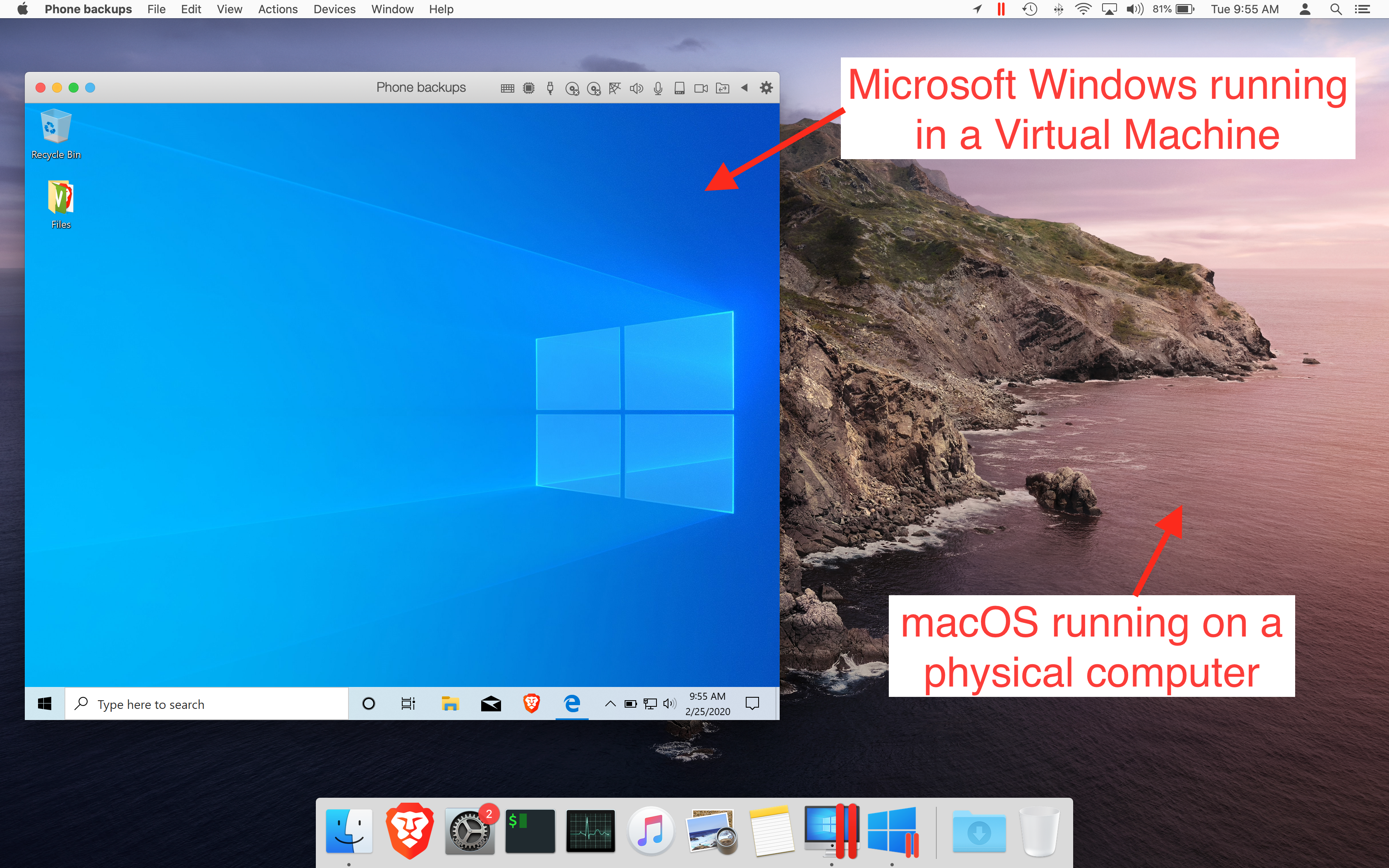

If you’re going with cloud servers, It’s important to understand the idea of virtual machines (or VMs). A virtual machine is a piece of software which acts like it’s a physical computer, even though it’s just software running on another computer. Here’s a picture of Microsoft Windows running inside of Virtual Machine software, which is in turn running on macOS, which is in turn running on a physical (Mac) computer:

When you rent servers from a cloud provider, you’re renting access to this kind of virtual machine, which is in turn running on the physical computers that the cloud company has installed in their datacenters. For your purposes, the machine you rent will act like a physical computer (though it may be slightly slower than a physical computer, since some of its hardware is emulated).

People sometimes refer to cloud virtual machines as “VMs”, “servers”, “nodes”, or “compute nodes”, and cloud providers have different “size” VMs you can rent. For instance, on the Azure Sponsorship account we get through OpenAI, Azure offers what they call “NC6_Promo” VMs, which each have 6 (virtual) CPUs and 1 GPU. The next size up that they offer is the “NC12_Promo”, which has 12 (virtual) CPUs and 2 GPUs. Then the next size up (and the maximum size we have access to) is an “NC24_Promo”, which has 12 (virtual) CPUs and 4 GPUs.

For reference, here are lists of popular Nvidia GPUs, in rough order of performance, as of early 2020:

Personal Computer Nvidia GPUs (fastest to slowest):

- RTX Titan

- RTX 2080 Ti

- RTX 2080 Super

- RTX 2080

- RTX 2070

- RTX 2060

- GTX 1080 Ti

- GTX 1080

- GTX 1070

- GTX 1650

- GTX 1060

Cloud GPUs (fastest to slowest):

- V100

- P100

- P4

- T4

- K80 (this is really just two K40 GPUs on one graphics card)

- K40

Limited benchmarks

As part of the OpenAI Scholars program, we receive some Microsoft Azure credit. I decided to use some of my credit to benchmark K40/80 GPUs against Google Colab and a GTX 1080 Ti in my home desktop: I built an image recognition network (similar to ResNet-34) and I trained it on a few thousand images. I timed each epoch and averaged them to get these numbers. Note that this may not quite reflect the performance of the actual video cards since all of the cloud benchmarks were running inside of virtual machines and the benchmark on my desktop was not:

| Server | GPU Kind | # GPUs | speed (lower is better) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azure NC6_Promo | K40 | 1 | 61.5 seconds |

| Google Colab | P100 | 1 | 37.0 seconds |

| Azure NC24_Promo | K40 | 4 | 22.4 seconds |

| Google Colab Pro | P100 | 1 | 22.4 seconds |

| My home desktop | 1080 Ti | 1 | 20.6 seconds |

Note that the Azure Servers technically have K80 graphics cards, but a K80 graphics card is just two K40 GPUs on one card, and Azure describes each virtual machine GPU as “Half of a K80”, which means in practice that they are K40s. Also note that the Google Colab Pro server had more RAM than the Google Colab free server did.

Bonus Round: TPUs

I mentioned above that Nvidia has a monopoly on deep learning GPUs. That’s true, but there is technically one other kind of hardware built for deep learning that you may want to know about: Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). TPUs are custom built by Google for deep learning and they’re only available to users through Google Cloud Platform and Google Collaboratory. TPUs are sufficiently restrictive that many deep learning programs built for GPUs won’t easily run on them, but if you can get your code to run on them, they’re much faster than even the fastest Nvidia GPUs. And they’re also available for free or very cheap through Colab, so it could be worth checking out!